In the previous articles

(“De-multiplexing of E1 stream: converting to C”,

“The mystery of an unstable performance”,

“How to make C run as fast as Java”,

“Size does matter”)

we converted the Java code for the de-multiplexing of E1 streams into C++ and played

a bit with compiler switches. We didn’t really optimise the programs – apart from resolving the pointer aliasing

issue, the code stayed intact. The switches helped improve speed, but Java has still not been beaten.

The top-performing C++ version is much smaller and more readable than the best Java version, but demonstrates

the same performance. We measure speed in milliseconds for one million iterations, and this value is 635 for both.

The versions we started with (the Reference) ran for 2860 ms in Java and 1939 in C++. This means we have

improved the speed quite a bit, but for an old C programmer it is hard to believe that this is the end.

There must be some ways to improve the speed in C. We’ll find these ways. Everything we’ve done so far

was just preparation; the real optimisation work only starts now. Get ready for an exciting ride.

The Non-portable land

The problem of de-multiplexing of the E1 stream is in fact the problem of the matrix transposition.

The elements separated by 32 bytes (the NUM_TIMESLOTS value) must end up next to each other, while the elements

next to each other must be written to the same position in different output arrays.

Until now we were achieving this by reading bytes from the source one at a time in some order and writing them (also one at a time) to the destination. We tried two orders: the source first and the destination first.

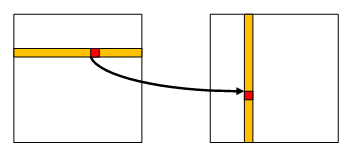

The source-first involves iterating the source matrix along the rows and writing elements along the columns:

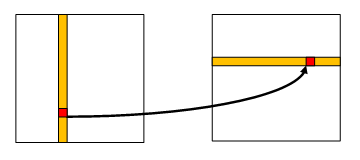

The destination-first works the other way around:

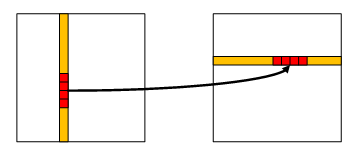

A natural improvement of both methods is to read (in case of the source-first) or to write (in case of the destination-first) more bytes at a time. Both methods can be easily modified for that. If this modification helps, we may consider doing both (read more and write more at a time), but this is obviously going to be more complex solution.

The natural size to start with is four bytes. Our previous experience helps to choose the direction.

The destination-first (Dst_First) family of versions has been the most successful so far, so let’s start there.

We’ll be writing four bytes at a time:

We must understand clearly that we are now entering a dangerous territory – the Non-portable land. Java programs are portable by the design of Java. Until now all our C programs were portable as well. They could run on every compiler and on every processor. From now on, it won’t work like this anymore. We are now going to construct four-byte units (double words) from individual bytes. This requires knowledge of the way double-words are stored in memory. This is called Endianness and differs between processors. All the code that follows will be written for so called ‘little-endian’ processors (Intel is one of those). This is the cost of the speed.

Writing 4 bytes at a time

Modifying the Dst_First to write four bytes at a time is almost a mechanical procedure. We unroll the inner loop

and then modify the writing (you can see the code in the repository):

inline uint32_t make_32 (byte b0, byte b1, byte b2, byte b3)

{

return ((uint32_t) b0 << 0)

| ((uint32_t) b1 << 8)

| ((uint32_t) b2 << 16)

| ((uint32_t) b3 << 24);

}

class Write4 : public Demux

{

public:

void demux (const byte * src, size_t src_length, byte ** dst) const

{

assert (src_length == NUM_TIMESLOTS * DST_SIZE);

assert (DST_SIZE % 4 == 0);

for (size_t dst_num = 0; dst_num < NUM_TIMESLOTS; ++ dst_num) {

byte * d = dst [dst_num];

for (size_t dst_pos = 0; dst_pos < DST_SIZE; dst_pos += 4) {

byte b0 = src [(dst_pos + 0) * NUM_TIMESLOTS + dst_num];

byte b1 = src [(dst_pos + 1) * NUM_TIMESLOTS + dst_num];

byte b2 = src [(dst_pos + 2) * NUM_TIMESLOTS + dst_num];

byte b3 = src [(dst_pos + 3) * NUM_TIMESLOTS + dst_num];

* (uint32_t*) & d [dst_pos] = make_32 (b0, b1, b2, b3);

}

}

}

};We have replaced four byte-write operations with one that writes a 32-bit word. This word is constructed from the four independently

read bytes, that’s why the whole procedure depends on the byte order of the word. The make_32 function is written

for a little-endian architecture; it must be replaced for a big-endian one. Note the type used. We can’t be sure that

any of integer types (short, int or long) is exactly 32 bits long. Fortunately, there are types, defined in

<stdint.h> (<cstdint> in case of C++), that occupy exactly the prescribed number of bits – 8, 16, 32 or 64.

Note the new assert: we must check that DST_SIZE is a multiple of 4, otherwise the function won’t work. Since

DST_SIZE is a constant, this assert can be checked at compile time and does not produce any code.

Our file e1.cpp became too long. Let’s start with a new file, called e1-new.cpp. We’ll compile it with the

same switches as e1.cpp:

# c++ -O3 -falign-functions=32 -falign-loops=32 -funroll-loops -o e1-new e1-new

.cpp -lrt

# ./e1-new

9Reference: 1406

6Write4: 491

As we can see, the change has caused an immediate effect: previously the shortest time was 635 ms. For the first time we’ve got a result that is better than that of the fully unrolled Java version.

Writing 8 bytes at a time

Our processor is a 64-bit one, so we can operate on 64-bit values as easily as on 32-bit ones. In particular, we can write 8 bytes at a time just like we did 4 in the previous version. Let’s make a version that reads 8 bytes separately and writes them all in one go.

inline uint64_t make_64 (byte b0, byte b1, byte b2, byte b3,

byte b4, byte b5, byte b6, byte b7)

{

return (uint64_t) make_32 (b0, b1, b2, b3)

| ((uint64_t) b4 << 32)

| ((uint64_t) b5 << 40)

| ((uint64_t) b6 << 48)

| ((uint64_t) b7 << 56);

}

class Write8 : public Demux

{

public:

void demux (const byte * src, size_t src_length, byte ** dst) const

{

assert (src_length == NUM_TIMESLOTS * DST_SIZE);

assert (DST_SIZE % 8 == 0);

for (size_t dst_num = 0; dst_num < NUM_TIMESLOTS; ++ dst_num) {

byte * d = dst [dst_num];

for (size_t dst_pos = 0; dst_pos < DST_SIZE; dst_pos += 8) {

byte b0 = src [(dst_pos + 0) * NUM_TIMESLOTS + dst_num];

byte b1 = src [(dst_pos + 1) * NUM_TIMESLOTS + dst_num];

byte b2 = src [(dst_pos + 2) * NUM_TIMESLOTS + dst_num];

byte b3 = src [(dst_pos + 3) * NUM_TIMESLOTS + dst_num];

byte b4 = src [(dst_pos + 4) * NUM_TIMESLOTS + dst_num];

byte b5 = src [(dst_pos + 5) * NUM_TIMESLOTS + dst_num];

byte b6 = src [(dst_pos + 6) * NUM_TIMESLOTS + dst_num];

byte b7 = src [(dst_pos + 7) * NUM_TIMESLOTS + dst_num];

* (uint64_t*) & d [dst_pos] = make_64 (b0, b1, b2, b3,

b4, b5, b6, b7);

}

}

}

};Running it, we get

6Write4: 494

6Write8: 508

This version is a bit slower than the Write4 - probably, the excessive amount of bit shifting isn’t

compensated by the reduction of memory writes.

Reading 4 bytes and writing 4 bytes at a time

Writing four bytes at a time made an improvement in speed. What about reading four bytes at a time as well?

We can read four uint32_t values, then break them down into bytes, re-assemble these bytes in the correct order and write

them back:

To write four bytes at a time we had to read four rows of the original matrix. Similarly, to read four bytes

at a time, we must write four rows of the resulting matrix. This means that we’ll have to maintain four of the d

pointers instead of one. Here is the code:

inline uint32_t byte0 (uint32_t x)

{

return x & 0xFF;

}

inline uint32_t byte1 (uint32_t x)

{

return (x >> 8) & 0xFF;

}

inline uint32_t byte2 (uint32_t x)

{

return (x >> 16) & 0xFF;

}

inline uint32_t byte3 (uint32_t x)

{

return (x >> 24) & 0xFF;

}

class Read4_Write4 : public Demux

{

public:

void demux (const byte * src, size_t src_length, byte ** dst) const

{

assert (src_length == NUM_TIMESLOTS * DST_SIZE);

assert (DST_SIZE % 4 == 0);

assert (NUM_TIMESLOTS % 4 == 0);

for (size_t dst_num = 0; dst_num < NUM_TIMESLOTS; dst_num += 4) {

byte * d0 = dst [dst_num + 0];

byte * d1 = dst [dst_num + 1];

byte * d2 = dst [dst_num + 2];

byte * d3 = dst [dst_num + 3];

for (size_t dst_pos = 0; dst_pos < DST_SIZE; dst_pos += 4) {

uint32_t w0 = * (uint32_t*) &src [(dst_pos + 0) * NUM_TIMESLOTS + dst_num];

uint32_t w1 = * (uint32_t*) &src [(dst_pos + 1) * NUM_TIMESLOTS + dst_num];

uint32_t w2 = * (uint32_t*) &src [(dst_pos + 2) * NUM_TIMESLOTS + dst_num];

uint32_t w3 = * (uint32_t*) &src [(dst_pos + 3) * NUM_TIMESLOTS + dst_num];

* (uint32_t*) &d0 [dst_pos] = make_32 (byte0 (w0), byte0 (w1), byte0 (w2), byte0 (w3));

* (uint32_t*) &d1 [dst_pos] = make_32 (byte1 (w0), byte1 (w1), byte1 (w2), byte1 (w3));

* (uint32_t*) &d2 [dst_pos] = make_32 (byte2 (w0), byte2 (w1), byte2 (w2), byte2 (w3));

* (uint32_t*) &d3 [dst_pos] = make_32 (byte3 (w0), byte3 (w1), byte3 (w2), byte3 (w3));

}

}

}

};Note that the procedure is as sensitive to the endianness of the processor as the Write4. To port it

to a big-endian processor, one would need to re-write byte0 .. byte3 routines as well as make32.

We also had to introduce another assert: on NUM_TIMESLOTS.

When running it, we get

6Write4: 491

6Write8: 507

12Read4_Write4: 686

It runs quite a bit slower than our existing versions. Analysing the code (I won’t show it here, it can be seen

in the repository, file e1-new.asm)

shows that both Write4 and Write8 have got their inner loop fully unrolled,

while Read4_Write4 have not. Obviously, we want to compare the results of the equally optimised versions.

We have a choice of the following options:

- try configuring the GNU C compiler to unroll all the loops in all the versions

- unroll all the functions manually and only keep the unrolled code

- write every function in two version – conventional and unrolled

- look at the code and write unrolled versions where the compiler didn’t unroll.

To keep it shorter, I’ll use the last option.

I’ll only write the unrolled code where the compiler doesn’t do the job,

and the code will only be available in the repository, except for this one. I’ll show the unrolled version

of Read4_Write4 here as an example (the full code is here):

class Read4_Write4_Unroll : public Demux

{

public:

void demux (const byte * src, size_t src_length, byte ** dst) const

{

assert (src_length == NUM_TIMESLOTS * DST_SIZE);

assert (DST_SIZE == 64);

assert (NUM_TIMESLOTS % 4 == 0);

for (size_t dst_num = 0; dst_num < NUM_TIMESLOTS; dst_num += 4) {

byte * d0 = dst [dst_num + 0];

byte * d1 = dst [dst_num + 1];

byte * d2 = dst [dst_num + 2];

byte * d3 = dst [dst_num + 3];

#define MOVE16(dst_pos) do {\

uint32_t w0 = * (uint32_t*) &src [(dst_pos + 0) * NUM_TIMESLOTS + dst_num];\

uint32_t w1 = * (uint32_t*) &src [(dst_pos + 1) * NUM_TIMESLOTS + dst_num];\

uint32_t w2 = * (uint32_t*) &src [(dst_pos + 2) * NUM_TIMESLOTS + dst_num];\

uint32_t w3 = * (uint32_t*) &src [(dst_pos + 3) * NUM_TIMESLOTS + dst_num];\

* (uint32_t*) &d0 [dst_pos] = make_32 (byte0 (w0), byte0 (w1), byte0 (w2), byte0 (w3));\

* (uint32_t*) &d1 [dst_pos] = make_32 (byte1 (w0), byte1 (w1), byte1 (w2), byte1 (w3));\

* (uint32_t*) &d2 [dst_pos] = make_32 (byte2 (w0), byte2 (w1), byte2 (w2), byte2 (w3));\

* (uint32_t*) &d3 [dst_pos] = make_32 (byte3 (w0), byte3 (w1), byte3 (w2), byte3 (w3));\

} while (0)

MOVE16 (0);

MOVE16 (4);

MOVE16 (8);

MOVE16 (12);

MOVE16 (16);

MOVE16 (20);

MOVE16 (24);

MOVE16 (28);

MOVE16 (32);

MOVE16 (36);

MOVE16 (40);

MOVE16 (44);

MOVE16 (48);

MOVE16 (52);

MOVE16 (56);

MOVE16 (60);

#undef MOVE16

}

}

};You can see that this version can be produced from the ununrolled one by a very simple transformation: the

inner loop becomes a macro with a single parameter dst_pos, and then this macro gets invoked with correct

values of dst_pos. This code is written for a specific value of DST_SIZE, that’s why it checks for it in an

assert.

The performance looks like this:

12Read4_Write4: 685

19Read4_Write4_Unroll: 638

The performance is still bad. The unrolling helped a bit; however, in general our wonderful plan has failed.

We could try more sophisticated versions, such as reading 4 bytes and writing 8, or even reading 8 and writing 8,

but there is little chance it will help. It looks like numerous shifts and bitwise ORs eat up all the performance gain

we get from optimising the memory access. It may seem that this is the end of our story, and there is

no way to make it faster, but we still have one more resource: the SSE.

Some words about the SSE

This article wasn’t conceived as an SSE tutorial. If you are unfamiliar with SSE, there are numerous resources where you can find something about it. The Wikipedia article can help for the initial reading; it explains different versions of SSE and their availability on various processors. As the ultimate reading, nothing can beat the Intel documentation, such as “Intel® 64 and IA-32 Architectures Software Developer Manuals” and “Intel® Architecture Instruction Set Extensions Programming Reference”, and there are many levels in between.

All the versions of the SSE are just extensions of the instruction set; that’s why the most natural way to use the SSE is writing in assembly language. Sometimes this is the only way; however, for most applications it is possible to do without it, because Intel was very kind to provide intrinsic functions for all the instructions, as well as for many combinations. This made it possible to program SSE while staying in C. Most C compilers in the Intel world understand these intrinsics. Both GNU C and MSVC do. Moreover, they are capable of performing optimisations on the SSE code so the code written in C may end up being better than a hand-written assembly code. Here is the Intel® guide for intrinsic functions.

One important thing to remember about SSE is that it makes our code even less portable. Until now our code could run on all little-endian processors, and it was very easy to modify it for a big-endian one. As soon as any SSE appears in the code, it becomes totally dependent on the Intel/AMD architecture. That’s why one must take care to mark this code accordingly and separate it from the universal code. The problem is aggravated by the fact that even on Intel the presence of the SSE is not guaranteed, and there are different versions of SSE (SSE, SSE2, SSE3, SSSE3, SSE4.1, SSE4.2, AVX, AVX2, FMA, etc.). The only relief comes from the fact that the 64-bit architecture was introduced later than the original SSE; as a result, every 64-bit platform supports at least the SSE2. Unfortunately, this is often not enough, for many useful instructions only appear in the later versions.

On the other hand, if someone is aiming for the best performance, the first thing to look at is the newest processor. This means that one can assume the presence of the most advanced instruction set when developing the fastest code. One unpleasant consequence is that one must redo the performance improvement exercise when a new processor is released; but this is the nature of the optimisation work. In particular, the work for this article was done on Sandy Bridge, whose limit is the AVX. When I get hold of a machine that supports AVX2, I’ll have to update the data.

If the target architecture is unknown, it makes sense developing several versions and choose between them dynamically. Our object-based design makes it easy. This approach is followed by Intel in their IPP library. Every function there comes in several versions, optimised for different processors. The most suitable version is chosen at run time.

In order to use the SSE intrinsics, one must include several header files. I’ve placed all such code in a special file,

sse.h. I also use this file as a collection of various handy utility functions and macros that will be created as

we go along.

And the last thing to remember before we start programming SSE is data alignment. The whole alignment story is a bit

complex, the requirements differ on different processors and in different modes of compilation. The penalties for

not aligning the data also differ. The most universal advice is to align data on 16 bytes for SSE and on

32 bytes for AVX. The new operator in GNU C aligns pointers by 16; however, some other compiler won’t necessarily

do it, so it is preferable to align pointers by 16 explicitly. SSE utility set has a special function for it,

_mm_malloc, where you can specify alignment, and corresponding _mm_free. We’ll definitely need to use these functions in

AVX case to align buffers by 32.

Reading 4 bytes and writing 4 bytes at a time using SSE

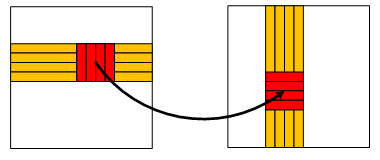

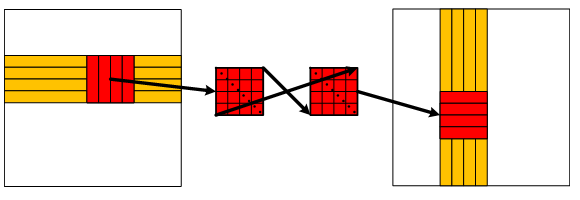

As we saw, the de-multiplexing of the E1 stream is essentially the transposition of a matrix. A natural way to transpose

a matrix is to read data in rectangular blocks, transpose these blocks and write them to the appropriate places

in the destination matrix. Our Read4 and Read8 versions used blocks of sizes 1×4 and 1×8, and the

Read4_Write4 version used 4×4 blocks:

The inner loop of Read4_Write4 transposes 4×4 blocks by calling

make32(), byte0(), byte1() and so on. If we look into the assembly code of Read4_Write4, we can see that this

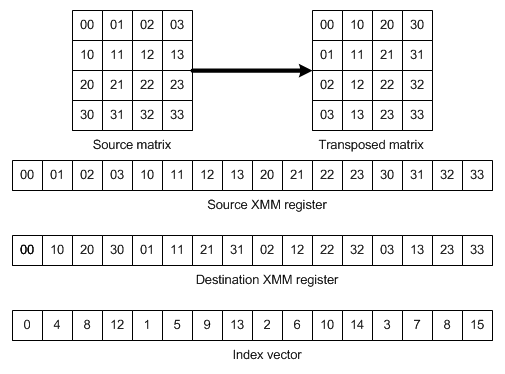

code is translated into a very long sequence of ORs and shifts. This is where SSE can help. It has a wonderful

instruction, the PSHUFB, which can shuffle the bytes inside the XMM register in any order. The order is defined

by another XMM register, where each byte contains an index in the argument for each byte of the result.

This instruction has been added in SSSE3 and is available via the _mm_shuffle_epi8 intrinsic. XMM registers

are 16 bytes long, and this suggests a plan: We’ll load the 4×4 matrix into one XMM register, shuffle it and write

the transposed matrix back.

The transposition routine looks like this:

inline __m128i transpose_4x4 (__m128i m)

{

return _mm_shuffle_epi8 (m, _mm_setr_epi8 (0, 4, 8, 12,

1, 5, 9, 13,

2, 6, 10, 14,

3, 7, 11, 15));

}One may ask: Why are we using _mm_setr_epi8 rather than _mm_set_epi8? This is because I use a different

byte order in my diagrams than Intel does in its documentation. They draw the SSE register with the highest byte first

(on the left side); for my purpose the memory layout order (the lowest address first) is more appropriate.

Intel calls this order “reverse”, and _mm_setr_epi8 loads byte in this reverse order. This difference only

applies to the presentation order and to the order of arguments of the “set” functions. It does not cause any

difference in the results of the operations. For instance, the zero index for the byte shuffle instruction points to

the lowest byte, which is the first byte in memory.

We still need to combine the original four double-words into a single XMM register and then extract resulting

double-words. Intel provides useful function _mm_setr_epi32() to do the first part (it is compiled into a sequence

of PINSRD (insert double-word) instructions). The second part can be done by PEXTRD (extract double word).

Both instructions are available since SSE4.1. Here is the code:

class Read4_Write4_SSE : public Demux

{

public:

void demux (const byte * src, size_t src_length, byte ** dst) const

{

assert (src_length == NUM_TIMESLOTS * DST_SIZE);

assert (DST_SIZE % 4 == 0);

assert (NUM_TIMESLOTS % 4 == 0);

for (size_t dst_num = 0; dst_num < NUM_TIMESLOTS; dst_num += 4) {

byte * d0 = dst [dst_num + 0];

byte * d1 = dst [dst_num + 1];

byte * d2 = dst [dst_num + 2];

byte * d3 = dst [dst_num + 3];

for (size_t dst_pos = 0; dst_pos < DST_SIZE; dst_pos += 4) {

uint32_t w0 = * (uint32_t*) &src [(dst_pos + 0) * NUM_TIMESLOTS + dst_num];

uint32_t w1 = * (uint32_t*) &src [(dst_pos + 1) * NUM_TIMESLOTS + dst_num];

uint32_t w2 = * (uint32_t*) &src [(dst_pos + 2) * NUM_TIMESLOTS + dst_num];

uint32_t w3 = * (uint32_t*) &src [(dst_pos + 3) * NUM_TIMESLOTS + dst_num];

__m128i m = _mm_setr_epi32 (w0, w1, w2, w3);

m = transpose_4x4 (m);

* (uint32_t*) &d0 [dst_pos] = (uint32_t) _mm_extract_epi32 (m, 0);

* (uint32_t*) &d1 [dst_pos] = (uint32_t) _mm_extract_epi32 (m, 1);

* (uint32_t*) &d2 [dst_pos] = (uint32_t) _mm_extract_epi32 (m, 2);

* (uint32_t*) &d3 [dst_pos] = (uint32_t) _mm_extract_epi32 (m, 3);

}

}

}

};Both PINSRD and PEXTRD instructions can work with the operands in memory, which makes the code especially efficient.

The compiler eliminates the w0, w1, w2, w3 variables and reads data straight into the parts of the XMM

registers. Later it extracts parts of the registers straight to memory. The code looks very neat.

We must compile the code with a switch that specifies the instruction set to use; in our case it will be SSE 4.2:

# c++ -O3 -msse4.2 -falign-functions=32 -falign-loops=32 -funroll-loops -o e1-n

ew e1-new.cpp -lrt

# ./e1-new

16Read4_Write4_SSE: 232

This is a huge improvement: from 638 ms for a non-SSE version to 232 for SSE. This is also a big improvement

compared to the fastest version before (Write4, 494 ms). In this case the unrolled version was

unnecessary – the compiler has already done all the work for us.

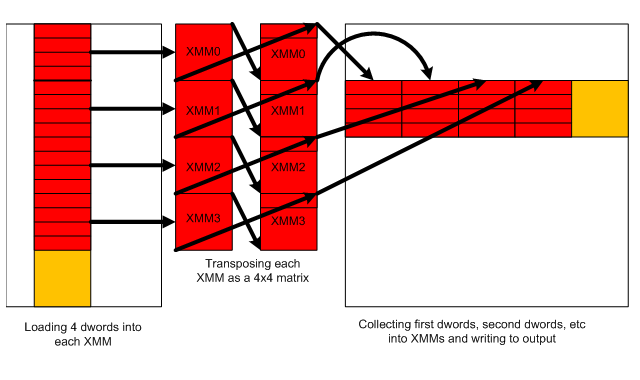

Reading 4 bytes and writing 16 bytes at a time using SSE

The usage of SSE looks very promising, so we can’t stop yet. What if we can improve performance by using even bigger blocks? The previous experience shows that writing 8 bytes at a time using regular registers doesn’t help much. Let’s be more ambitious and write 16 bytes at a time.

This is what we’ll be doing:

We’ll be reading a 4×16 matrix, transpose it and write as 16×4 matrix (see the code):

template<unsigned i> inline __m128i combine_sse (__m128i m0, __m128i m1, __m128i m2, __m128i m3)

{

__m128i x = _128i_shuffle (m0, m1, i, i, i, i); // m0[i] m0[i] m1[i] m1[i]

__m128i y = _128i_shuffle (m2, m3, i, i, i, i); // m2[i] m2[i] m3[i] m3[i]

return _128i_shuffle (x, y, 0, 2, 0, 2);

}

class Read4_Write16_SSE : public Demux

{

public:

void demux (const byte * src, size_t src_length, byte ** dst) const

{

assert (src_length == NUM_TIMESLOTS * DST_SIZE);

assert (DST_SIZE % 16 == 0);

assert (NUM_TIMESLOTS % 4 == 0);

for (size_t dst_num = 0; dst_num < NUM_TIMESLOTS; dst_num += 4) {

byte * d0 = dst [dst_num + 0];

byte * d1 = dst [dst_num + 1];

byte * d2 = dst [dst_num + 2];

byte * d3 = dst [dst_num + 3];

for (size_t dst_pos = 0; dst_pos < DST_SIZE; dst_pos += 16) {

#define LOAD16(m, dst_pos) do {\

uint32_t w0 = * (uint32_t*) &src [(dst_pos + 0) * NUM_TIMESLOTS + dst_num];\

uint32_t w1 = * (uint32_t*) &src [(dst_pos + 1) * NUM_TIMESLOTS + dst_num];\

uint32_t w2 = * (uint32_t*) &src [(dst_pos + 2) * NUM_TIMESLOTS + dst_num];\

uint32_t w3 = * (uint32_t*) &src [(dst_pos + 3) * NUM_TIMESLOTS + dst_num];\

m = _mm_setr_epi32 (w0, w1, w2, w3);\

m = transpose_4x4 (m);\

} while (0)

__m128i m0, m1, m2, m3;

LOAD16 (m0, dst_pos);

LOAD16 (m1, dst_pos + 4);

LOAD16 (m2, dst_pos + 8);

LOAD16 (m3, dst_pos + 12);

_128i_store (&d0 [dst_pos], combine_sse<0> (m0, m1, m2, m3));

_128i_store (&d1 [dst_pos], combine_sse<1> (m0, m1, m2, m3));

_128i_store (&d2 [dst_pos], combine_sse<2> (m0, m1, m2, m3));

_128i_store (&d3 [dst_pos], combine_sse<3> (m0, m1, m2, m3));

#undef LOAD16

}

}

}

};The LOAD16 macro loads four rows of four bytes each, merges them together into a XMM variable and performs

a 4×4 transposition. When all the 16 inputs are ready and placed into four XMM registers, we must write them to

the output, but only after additional re-shuffling. The shuffling is needed because our XMM registers

at this point represent 4×4 matrices, and we need to collect the first row of all the matrices, then the

second and so on. This shuffling is done by the template function combine_sse, where the template parameter

indicates the row number.

Some additional comments are needed at this point.

Shuffling of the 32-bit values in SSE is done by the PSHUFD instruction (SSE2), which is available

via the intrinsic _mm_shuffle_epi32(). This instruction takes two sources and a control value,

which consists of four constant values n0, n1, n2, n3. Each of these values occupies two bits, and they are packed in a

byte. This is what the instruction does: if A is the first argument (seen as an array of 4 double-words),

and B is the second one, then the instruction produces the following result:

A[n0] A[n1] B[n2] B[n3]

As a result, we need three of these instructions to collect components with the same indices from four sources.

_128i_shuffle is my own service macro, which takes care of packing values n0, n1, n2, n3 into a byte.

It had to be made a macro rather than an inline function, because it only allows constants as the n parameters,

and there is no way to declare that in C++. For the same reason the combine_sse is made a template:

the row number must be a constant. These macros and functions can be seen in the sse.h.

This is what we get when we run it:

17Read4_Write16_SSE: 193

This is already much better than Read4_Write4, but there is a very easy way to make it faster without touching the code.

Remember, we are running on the Sandy Bridge processor. This processor supports AVX, and AVX, apart from proper AVX

instructions, has a new way of encoding the SSE instructions. These instructions start with the letter ‘V” and use three

arguments instead of two. Traditional SSE requires the result to be in the same place as the first argument,

while AVX allows it to be in a different register. This can save a transfer instruction and make execution faster.

Here is an example:

The insert instruction in SSE:

PINSRD xmm1, r/m32, imm8The same instruction in AVX encoded with VEX prefix:

VPINSRD xmm1, xmm2, r32/m32, imm8Both instructions insert a 32-bit word at a given position into the argument, but the second one can put its result into another register, while the first one must put it back into the first argument.

Let’s try this encoding mode:

# c++ -O3 -mavx -falign-functions=32 -falign-loops=32 -funroll-loops -o e1-new

e1-new.cpp -lrt

# ./e1-new

17Read4_Write16_SSE: 164

(files e1-new-sse.asm and e1-new-avx.asm in the repository contain old and new generated code).

Just one switch gave us quite a substantial gain. The result is 68 ms (29%) faster than the best previous result and four times faster than what we started with. Can one ask for more?

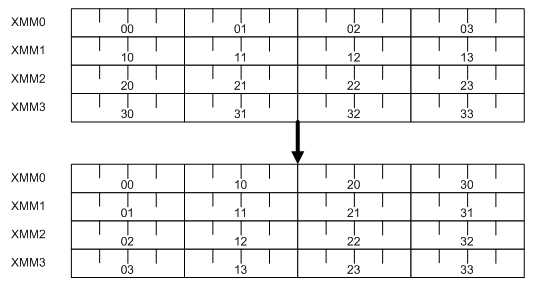

There are two observations that make us believe we can do better. First, the four calls to combine_sse look

very similar to the four calls to make_32 in Read4_Write4. In that case these calls in fact performed

transposition of a 4×4 matrix of bytes. In our new case the new four calls perform transposition of a 4×4

matrix of double-words (units of 4 bytes):

If we could find better way to transpose a byte matrix, perhaps we can find a better way to transpose a double-word matrix?

The second observation gives a hint on this better way. Look at the first lines of _combine_sse:

__m128i x = _128i_shuffle (m0, m1, i, i, i, i); // m0[i] m0[i] m1[i] m1[i]We are using identical values (i) for all four parameters, as a result we get a vector where the first two components

are the same and so are the last two. In the last line of the function only two of these components are

used; the others are ignored. In other words, wasted. The shuffle instruction only produced half of what it

could deliver. If we manage to put something meaningful into the positions 1 and 3 of the result of this shuffle,

we can potentially use less instructions. What is needed is to perform all the shuffles together, rather than each

row on its own. Here is the code:

inline void transpose_4x4_dwords (__m128i &w0, __m128i &w1, __m128i &w2, __m128i &w3)

{

// w0 = 0 1 2 3

// w1 = 4 5 6 7

// w2 = 8 9 10 11

// w3 = 12 13 14 15

__m128i x0 = _128i_shuffle (w0, w1, 0, 1, 0, 1); // 0 1 4 5

__m128i x1 = _128i_shuffle (w0, w1, 2, 3, 2, 3); // 2 3 6 7

__m128i x2 = _128i_shuffle (w2, w3, 0, 1, 0, 1); // 8 9 12 13

__m128i x3 = _128i_shuffle (w2, w3, 2, 3, 2, 3); // 10 11 14 15

w0 = _128i_shuffle (x0, x2, 0, 2, 0, 2); // 0 4 8 12

w1 = _128i_shuffle (x0, x2, 1, 3, 1, 3); // 1 5 9 13

w2 = _128i_shuffle (x1, x3, 0, 2, 0, 2); // 2 6 10 14

w3 = _128i_shuffle (x1, x3, 1, 3, 1, 3); // 3 7 11 15

}We have used eight shuffle instructions where previously we were using twelve. Hopefully, this will make a difference.

Let’s modify the Read4_Write16_SSE (the new code is here):

class Read4_Write16_SSE : public Demux

{

public:

void demux (const byte * src, size_t src_length, byte ** dst) const

{

assert (src_length == NUM_TIMESLOTS * DST_SIZE);

assert (DST_SIZE % 16 == 0);

assert (NUM_TIMESLOTS % 4 == 0);

for (size_t dst_num = 0; dst_num < NUM_TIMESLOTS; dst_num += 4) {

byte * d0 = dst [dst_num + 0];

byte * d1 = dst [dst_num + 1];

byte * d2 = dst [dst_num + 2];

byte * d3 = dst [dst_num + 3];

for (size_t dst_pos = 0; dst_pos < DST_SIZE; dst_pos += 16) {

#define LOAD16(m, dst_pos) do {\

uint32_t w0 = * (uint32_t*) &src [(dst_pos + 0) * NUM_TIMESLOTS + dst_num];\

uint32_t w1 = * (uint32_t*) &src [(dst_pos + 1) * NUM_TIMESLOTS + dst_num];\

uint32_t w2 = * (uint32_t*) &src [(dst_pos + 2) * NUM_TIMESLOTS + dst_num];\

uint32_t w3 = * (uint32_t*) &src [(dst_pos + 3) * NUM_TIMESLOTS + dst_num];\

m = _mm_setr_epi32 (w0, w1, w2, w3);\

m = transpose_4x4 (m);\

} while (0)

__m128i m0, m1, m2, m3;

LOAD16 (m0, dst_pos);

LOAD16 (m1, dst_pos + 4);

LOAD16 (m2, dst_pos + 8);

LOAD16 (m3, dst_pos + 12);

transpose_4x4_dwords (m0, m1, m2, m3);

_128i_store (&d0 [dst_pos], m0);

_128i_store (&d1 [dst_pos], m1);

_128i_store (&d2 [dst_pos], m2);

_128i_store (&d3 [dst_pos], m3);

#undef LOAD16

}

}

}

};And the result is

17Read4_Write16_SSE: 141

This gives us another 23 ms, or 14%. It will really be hard to beat this result!

Reading 8 bytes and writing 16 bytes at a time using SSE

We’ve seen that writing 16 bytes at a time using SSE registers helped a lot. We are not going to stop here, however. What if we try reading 8 bytes at a time? It was slower than the 4-byte version in the non-SSE case, but what if the SSE will change something?

Obviously, if we read 8 bytes from each line, we must write 8 lines at a time. Each 8-byte value must be split in two, the first (low) 4 bytes written to the first 4 lines of the output and the next (high) 4 bytes to the next 4 lines (I won’t draw the diagram, for it will complicate matters more than explain them). We can duplicate the existing code to process 8 bytes at a time (see here):

uint32_t low (uint64_t x)

{

return (uint32_t) x;

}

uint32_t high (uint64_t x)

{

return (uint32_t) (x >> 32);

}

class Read8_Write16_SSE : public Demux

{

public:

void demux (const byte * src, size_t src_length, byte ** dst) const

{

assert (src_length == NUM_TIMESLOTS * DST_SIZE);

assert (DST_SIZE % 16 == 0);

assert (NUM_TIMESLOTS % 8 == 0);

for (size_t dst_num = 0; dst_num < NUM_TIMESLOTS; dst_num += 8) {

byte * d0 = dst [dst_num + 0];

byte * d1 = dst [dst_num + 1];

byte * d2 = dst [dst_num + 2];

byte * d3 = dst [dst_num + 3];

byte * d4 = dst [dst_num + 4];

byte * d5 = dst [dst_num + 5];

byte * d6 = dst [dst_num + 6];

byte * d7 = dst [dst_num + 7];

for (size_t dst_pos = 0; dst_pos < DST_SIZE; dst_pos += 16) {

#define LOAD32(m0, m1, dst_pos) do {\

uint64_t w0 = * (uint64_t*) &src [(dst_pos + 0) * NUM_TIMESLOTS + dst_num];\

uint64_t w1 = * (uint64_t*) &src [(dst_pos + 1) * NUM_TIMESLOTS + dst_num];\

uint64_t w2 = * (uint64_t*) &src [(dst_pos + 2) * NUM_TIMESLOTS + dst_num];\

uint64_t w3 = * (uint64_t*) &src [(dst_pos + 3) * NUM_TIMESLOTS + dst_num];\

m0 = _mm_setr_epi32 (low (w0), low (w1), low (w2), low (w3));\

m1 = _mm_setr_epi32 (high (w0), high (w1), high (w2), high (w3));\

m0 = transpose_4x4 (m0);\

m1 = transpose_4x4 (m1);\

} while (0)

__m128i a0, a1, a2, a3, b0, b1, b2, b3;

LOAD32 (a0, b0, dst_pos);

LOAD32 (a1, b1, dst_pos + 4);

LOAD32 (a2, b2, dst_pos + 8);

LOAD32 (a3, b3, dst_pos + 12);

transpose_4x4_dwords (a0, a1, a2, a3);

_128i_store (&d0 [dst_pos], a0);

_128i_store (&d1 [dst_pos], a1);

_128i_store (&d2 [dst_pos], a2);

_128i_store (&d3 [dst_pos], a3);

transpose_4x4_dwords (b0, b1, b2, b3);

_128i_store (&d4 [dst_pos], b0);

_128i_store (&d5 [dst_pos], b1);

_128i_store (&d6 [dst_pos], b2);

_128i_store (&d7 [dst_pos], b3);

#undef LOAD32

}

}

}

};This code can be produced from the code of Read4_Write16_SSE by a mechanical transformation: we first unroll the inner

loop, then move the loads from the second copy of the loop body up and put them next to the loads from the first

copy. Finally, each pair of loads may be replaced by a single 64-bit load.

Here is the result we’ve got:

17Read8_Write16_SSE: 205

The code hasn’t been unrolled, so we need an unrolled version:

24Read8_Write16_SSE_Unroll: 202

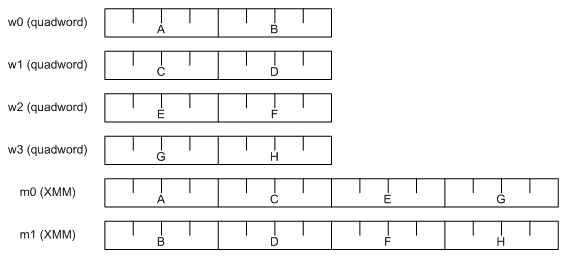

As we see, the 64-bit loads didn’t help at all. The performance is much worse than what we achieved before. However, there is one possibility for improvement. Here we read 8-byte values, split them in halves and then populate SSE registers. Schematically it looks like this:

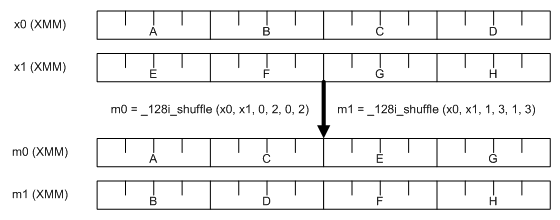

The alternative way to achieve the same is to place 8-byte values straight into SSE registers and perform splitting there by means of shuffling:

The easiest way to combine two 8-byte values into a 16-byte register is via the

intrinsic _mm_setr_epi64. It is implemented using MOVQ and PINSRQ instructions. It takes __m64 parameters

rather than _uint64_t, so we’ll need to declare the variables differently.

Here is the code:

class Read8_Write16_SSE : public Demux

{

public:

void demux (const byte * src, size_t src_length, byte ** dst) const

{

assert (src_length == NUM_TIMESLOTS * DST_SIZE);

assert (DST_SIZE % 16 == 0);

assert (NUM_TIMESLOTS % 8 == 0);

for (size_t dst_num = 0; dst_num < NUM_TIMESLOTS; dst_num += 8) {

byte * d0 = dst [dst_num + 0];

byte * d1 = dst [dst_num + 1];

byte * d2 = dst [dst_num + 2];

byte * d3 = dst [dst_num + 3];

byte * d4 = dst [dst_num + 4];

byte * d5 = dst [dst_num + 5];

byte * d6 = dst [dst_num + 6];

byte * d7 = dst [dst_num + 7];

for (size_t dst_pos = 0; dst_pos < DST_SIZE; dst_pos += 16) {

#define LOAD32(m0, m1, dst_pos) do {\

__m64 w0 = * (__m64 *) &src [(dst_pos + 0) * NUM_TIMESLOTS + dst_num];\

__m64 w1 = * (__m64 *) &src [(dst_pos + 1) * NUM_TIMESLOTS + dst_num];\

__m64 w2 = * (__m64 *) &src [(dst_pos + 2) * NUM_TIMESLOTS + dst_num];\

__m64 w3 = * (__m64 *) &src [(dst_pos + 3) * NUM_TIMESLOTS + dst_num];\

__m128i x0 = _mm_setr_epi64 (w0, w1);\

__m128i x1 = _mm_setr_epi64 (w2, w3);\

m0 = _128i_shuffle (x0, x1, 0, 2, 0, 2);\

m1 = _128i_shuffle (x0, x1, 1, 3, 1, 3);\

m0 = transpose_4x4 (m0);\

m1 = transpose_4x4 (m1);\

} while (0)

__m128i a0, a1, a2, a3, b0, b1, b2, b3;

LOAD32 (a0, b0, dst_pos);

LOAD32 (a1, b1, dst_pos + 4);

LOAD32 (a2, b2, dst_pos + 8);

LOAD32 (a3, b3, dst_pos + 12);

transpose_4x4_dwords (a0, a1, a2, a3);

_128i_store (&d0 [dst_pos], a0);

_128i_store (&d1 [dst_pos], a1);

_128i_store (&d2 [dst_pos], a2);

_128i_store (&d3 [dst_pos], a3);

transpose_4x4_dwords (b0, b1, b2, b3);

_128i_store (&d4 [dst_pos], b0);

_128i_store (&d5 [dst_pos], b1);

_128i_store (&d6 [dst_pos], b2);

_128i_store (&d7 [dst_pos], b3);

#undef LOAD32

}

}

}

};The shuffle instructions inside the macro do what we were previously doing by splitting 64-bit values in two

using low() and high().

Here is the result:

18Read8c_Write16_SSE: 124

25Read8c_Write16_SSE_Unroll: 120

This gives us another 21 ms, making our code incredibly fast.

How about reading 16 and writing 16?

Since working with 8×16 blocks was so successful, it seems attractive to use 16×16 blocks. What if we read a 16x16 block into 16 SSE registers, transpose this block and write to the output?

I’ve tried this. This was a monster of a code. I’m not going to publish it here,

but you can see it in the repository

(versions Read16_Write16_SSE and Read16-Write16_SSE_Unroll). And this was the result:

18Read16_Write16_SSE: 176

25Read16_Write16_SSE_Unroll: 163

It would have been considered a great success when I started with the article, but now we have much better result

available – that from the Read8_Write16_SSE (120 ms). I can see two reasons why the new results are so bad. One is that

we have only 16 general purpose registers, so keeping 16 destination pointers occupies them all. This leaves no

registers for loop counters and other temporary needs. The other reason is that there are only 16 XMM registers,

and all 16 are used for the loaded values, leaving no space for temporary results. This causes extensive

register spill,

which slows everything down. It looks as if working with 8 values is our best option.

Reading 4 bytes and writing 32 bytes using AVX

Now it’s time to try AVX. AVX works with 32-byte registers called YMM. As in the SSE case, there are 16 of them. There are 32-byte loads and stores, and most of 16-byte operations have 32-byte versions, with some restrictions. The byte shuffle instruction isn’t available in AVX, and double-word shuffle works differently. The source 32-byte registers are considered pairs of 16-byte values, called lanes, and identical shuffling is applied to both lanes.

It is easy to change a 16-byte (SSE) version into a 32-byte AVX version. All that’s needed is to duplicate the loop body (unroll the loop), combine together 16-byte values from even and odd iterations and write the resulting 32-byte values to the output. Here is the code:

inline __m256i _256i_combine_lo_hi (__m128i lo, __m128i hi)

{

__m256i a = _mm256_setzero_si256 ();

a = _mm256_insertf128_si256 (a, lo, 0);

a = _mm256_insertf128_si256 (a, hi, 1);

return a;

}

class Read4_Write32_AVX : public Demux

{

public:

void demux (const byte * src, size_t src_length, byte ** dst) const

{

assert (src_length == NUM_TIMESLOTS * DST_SIZE);

assert (DST_SIZE % 32 == 0);

assert (NUM_TIMESLOTS % 4 == 0);

for (size_t dst_num = 0; dst_num < NUM_TIMESLOTS; dst_num += 4) {

byte * d0 = dst [dst_num + 0];

byte * d1 = dst [dst_num + 1];

byte * d2 = dst [dst_num + 2];

byte * d3 = dst [dst_num + 3];

for (size_t dst_pos = 0; dst_pos < DST_SIZE; dst_pos += 32) {

#define LOAD16(m, dst_pos) do {\

uint32_t w0 = * (uint32_t*) &src [(dst_pos + 0) * NUM_TIMESLOTS + dst_num];\

uint32_t w1 = * (uint32_t*) &src [(dst_pos + 1) * NUM_TIMESLOTS + dst_num];\

uint32_t w2 = * (uint32_t*) &src [(dst_pos + 2) * NUM_TIMESLOTS + dst_num];\

uint32_t w3 = * (uint32_t*) &src [(dst_pos + 3) * NUM_TIMESLOTS + dst_num];\

m = _mm_setr_epi32 (w0, w1, w2, w3);\

m = transpose_4x4 (m);\

} while (0)

__m128i a0, a1, a2, a3;

LOAD16 (a0, dst_pos);

LOAD16 (a1, dst_pos + 4);

LOAD16 (a2, dst_pos + 8);

LOAD16 (a3, dst_pos + 12);

transpose_4x4_dwords (a0, a1, a2, a3);

__m128i b0, b1, b2, b3;

LOAD16 (b0, dst_pos + 16);

LOAD16 (b1, dst_pos + 20);

LOAD16 (b2, dst_pos + 24);

LOAD16 (b3, dst_pos + 28);

transpose_4x4_dwords (b0, b1, b2, b3);

_256i_store (&d0 [dst_pos], _256i_combine_lo_hi (a0, b0));

_256i_store (&d1 [dst_pos], _256i_combine_lo_hi (a1, b1));

_256i_store (&d2 [dst_pos], _256i_combine_lo_hi (a2, b2));

_256i_store (&d3 [dst_pos], _256i_combine_lo_hi (a3, b3));

#undef LOAD16

}

}

}

};Before running it we must include the AVX header (immintrin.h) in sse.h, and not forget to modify alignment

of data (AVX requires 32 bytes). We’ve already been compiling using -mavx switch, so nothing has to change there.

Here is the result:

17Read4_Write32_AVX: 155

This result doesn’t look very impressive – we know we can do faster than this. But a careful look at the code shows that

there is a way to improve it. We transpose 16-byte values separately and only combine them together right before

writing to the output. This way we only use AVX memory write capability and not it’s processing.

But as I said earlier, the AVX is capable of performing two parallel, identical shuffles on

two 16-byte portions of a register. This is exactly what we need. We’ll create a 32-byte version of transpose_4x4_dwords:

inline void transpose_avx_4x4_dwords (__m256i &w0, __m256i &w1, __m256i &w2, __m256i &w3)

{

// 0 1 2 3

// 4 5 6 7

// 8 9 10 11

// 12 13 14 15

__m256i x0 = _256i_shuffle (w0, w1, 0, 1, 0, 1); // 0 1 4 5

__m256i x1 = _256i_shuffle (w0, w1, 2, 3, 2, 3); // 2 3 6 7

__m256i x2 = _256i_shuffle (w2, w3, 0, 1, 0, 1); // 8 9 12 13

__m256i x3 = _256i_shuffle (w2, w3, 2, 3, 2, 3); // 10 11 14 15

w0 = _256i_shuffle (x0, x2, 0, 2, 0, 2); // 0 4 8 12

w1 = _256i_shuffle (x0, x2, 1, 3, 1, 3); // 1 5 9 13

w2 = _256i_shuffle (x1, x3, 0, 2, 0, 2); // 2 6 10 14

w3 = _256i_shuffle (x1, x3, 1, 3, 1, 3); // 3 7 11 15

}class Read4_Write32_AVX : public Demux

{

public:

void demux (const byte * src, size_t src_length, byte ** dst) const

{

assert (src_length == NUM_TIMESLOTS * DST_SIZE);

assert (DST_SIZE % 32 == 0);

assert (NUM_TIMESLOTS % 4 == 0);

for (size_t dst_num = 0; dst_num < NUM_TIMESLOTS; dst_num += 4) {

byte * d0 = dst [dst_num + 0];

byte * d1 = dst [dst_num + 1];

byte * d2 = dst [dst_num + 2];

byte * d3 = dst [dst_num + 3];

for (size_t dst_pos = 0; dst_pos < DST_SIZE; dst_pos += 32) {

#define LOAD16(m, dst_pos) do {\

uint32_t w0 = * (uint32_t*) &src [(dst_pos + 0) * NUM_TIMESLOTS + dst_num];\

uint32_t w1 = * (uint32_t*) &src [(dst_pos + 1) * NUM_TIMESLOTS + dst_num];\

uint32_t w2 = * (uint32_t*) &src [(dst_pos + 2) * NUM_TIMESLOTS + dst_num];\

uint32_t w3 = * (uint32_t*) &src [(dst_pos + 3) * NUM_TIMESLOTS + dst_num];\

m = _mm_setr_epi32 (w0, w1, w2, w3);\

m = transpose_4x4 (m);\

} while (0)

__m128i a0, a1, a2, a3;

LOAD16 (a0, dst_pos);

LOAD16 (a1, dst_pos + 4);

LOAD16 (a2, dst_pos + 8);

LOAD16 (a3, dst_pos + 12);

__m128i b0, b1, b2, b3;

LOAD16 (b0, dst_pos + 16);

LOAD16 (b1, dst_pos + 20);

LOAD16 (b2, dst_pos + 24);

LOAD16 (b3, dst_pos + 28);

__m256i w0 = _256i_combine_lo_hi (a0, b0);

__m256i w1 = _256i_combine_lo_hi (a1, b1);

__m256i w2 = _256i_combine_lo_hi (a2, b2);

__m256i w3 = _256i_combine_lo_hi (a3, b3);

transpose_avx_4x4_dwords (w0, w1, w2, w3);

_256i_store (&d0 [dst_pos], w0);

_256i_store (&d1 [dst_pos], w1);

_256i_store (&d2 [dst_pos], w2);

_256i_store (&d3 [dst_pos], w3);

#undef LOAD16

}

}

}

};This the speed we get:

17Read4_Write32_AVX: 138

This is much better but still not great. We’ll have to do the last effort.

Reading 8 bytes and writing 32 bytes using AVX

Writing this version is rather straightforward. We just combine the approaches from Read8_Write16_SSE

and Read4_Write32_AVX. Here is the code:

class Read8_Write32_AVX : public Demux

{

public:

void demux (const byte * src, size_t src_length, byte ** dst) const

{

assert (src_length == NUM_TIMESLOTS * DST_SIZE);

assert (DST_SIZE % 32 == 0);

assert (NUM_TIMESLOTS % 8 == 0);

for (size_t dst_num = 0; dst_num < NUM_TIMESLOTS; dst_num += 8) {

byte * d0 = dst [dst_num + 0];

byte * d1 = dst [dst_num + 1];

byte * d2 = dst [dst_num + 2];

byte * d3 = dst [dst_num + 3];

byte * d4 = dst [dst_num + 4];

byte * d5 = dst [dst_num + 5];

byte * d6 = dst [dst_num + 6];

byte * d7 = dst [dst_num + 7];

for (size_t dst_pos = 0; dst_pos < DST_SIZE; dst_pos += 32) {

#define LOAD32(m0, m1, dst_pos) do {\

__m64 w0 = * (__m64 *) &src [(dst_pos + 0) * NUM_TIMESLOTS + dst_num];\

__m64 w1 = * (__m64 *) &src [(dst_pos + 1) * NUM_TIMESLOTS + dst_num];\

__m64 w2 = * (__m64 *) &src [(dst_pos + 2) * NUM_TIMESLOTS + dst_num];\

__m64 w3 = * (__m64 *) &src [(dst_pos + 3) * NUM_TIMESLOTS + dst_num];\

__m128i x0 = _mm_setr_epi64 (w0, w1);\

__m128i x1 = _mm_setr_epi64 (w2, w3);\

m0 = _128i_shuffle (x0, x1, 0, 2, 0, 2);\

m1 = _128i_shuffle (x0, x1, 1, 3, 1, 3);\

m0 = transpose_4x4 (m0);\

m1 = transpose_4x4 (m1);\

} while (0)

__m128i a0, a1, a2, a3, b0, b1, b2, b3;

LOAD32 (a0, b0, dst_pos);

LOAD32 (a1, b1, dst_pos + 4);

LOAD32 (a2, b2, dst_pos + 8);

LOAD32 (a3, b3, dst_pos + 12);

__m128i c0, c1, c2, c3, e0, e1, e2, e3;

LOAD32 (c0, e0, dst_pos + 16);

LOAD32 (c1, e1, dst_pos + 20);

LOAD32 (c2, e2, dst_pos + 24);

LOAD32 (c3, e3, dst_pos + 28);

__m256i w0 = _256i_combine_lo_hi (a0, c0);

__m256i w1 = _256i_combine_lo_hi (a1, c1);

__m256i w2 = _256i_combine_lo_hi (a2, c2);

__m256i w3 = _256i_combine_lo_hi (a3, c3);

__m256i w4 = _256i_combine_lo_hi (b0, e0);

__m256i w5 = _256i_combine_lo_hi (b1, e1);

__m256i w6 = _256i_combine_lo_hi (b2, e2);

__m256i w7 = _256i_combine_lo_hi (b3, e3);

transpose_avx_4x4_dwords (w0, w1, w2, w3);

_256i_store (&d0 [dst_pos], w0);

_256i_store (&d1 [dst_pos], w1);

_256i_store (&d2 [dst_pos], w2);

_256i_store (&d3 [dst_pos], w3);

transpose_avx_4x4_dwords (w4, w5, w6, w7);

_256i_store (&d4 [dst_pos], w4);

_256i_store (&d5 [dst_pos], w5);

_256i_store (&d6 [dst_pos], w6);

_256i_store (&d7 [dst_pos], w7);

#undef LOAD32

}

}

}

};Here is the speed:

17Read8_Write32_AVX: 112

Some inefficiency is still visible in the code. Initial shuffles (inside the LOAD32 macro) are still performed

separately on 128-bit registers rather than together in 256-bit register. Unfortunately, they are followed by

the _mm_shuffle_epi8 instruction (in transpose_4x4), which is not available in AVX. The 256-bit values would have

to be split in two before invoking this instruction and the halves re-assembled after. I tried this, the result is

slower than what we’ve just achieved.

However, the byte-shuffle instruction is available on AVX2. When I get hold of a processor with AVX2 (such as Haswell), I’ll update the data.

The winner

The compiler didn’t unroll the code of the previous version. We’ll have to do it manually. I promised not to publish the unrolled versions, but this is a special case – we must look at the absolute winner of this race:

class Read8_Write32_AVX_Unroll : public Demux

{

public:

void demux (const byte * src, size_t src_length, byte ** dst) const

{

assert (src_length == NUM_TIMESLOTS * DST_SIZE);

assert (DST_SIZE == 64);

assert (NUM_TIMESLOTS % 8 == 0);

for (size_t dst_num = 0; dst_num < NUM_TIMESLOTS; dst_num += 8) {

byte * d0 = dst [dst_num + 0];

byte * d1 = dst [dst_num + 1];

byte * d2 = dst [dst_num + 2];

byte * d3 = dst [dst_num + 3];

byte * d4 = dst [dst_num + 4];

byte * d5 = dst [dst_num + 5];

byte * d6 = dst [dst_num + 6];

byte * d7 = dst [dst_num + 7];

#define LOAD32(m0, m1, dst_pos) do {\

__m64 w0 = * (__m64 *) &src [(dst_pos + 0) * NUM_TIMESLOTS + dst_num];\

__m64 w1 = * (__m64 *) &src [(dst_pos + 1) * NUM_TIMESLOTS + dst_num];\

__m64 w2 = * (__m64 *) &src [(dst_pos + 2) * NUM_TIMESLOTS + dst_num];\

__m64 w3 = * (__m64 *) &src [(dst_pos + 3) * NUM_TIMESLOTS + dst_num];\

__m128i x0 = _mm_setr_epi64 (w0, w1);\

__m128i x1 = _mm_setr_epi64 (w2, w3);\

m0 = _128i_shuffle (x0, x1, 0, 2, 0, 2);\

m1 = _128i_shuffle (x0, x1, 1, 3, 1, 3);\

m0 = transpose_4x4 (m0);\

m1 = transpose_4x4 (m1);\

} while (0)

#define MOVE256(dst_pos) do {\

__m128i a0, a1, a2, a3, b0, b1, b2, b3;\

LOAD32 (a0, b0, dst_pos);\

LOAD32 (a1, b1, dst_pos + 4);\

LOAD32 (a2, b2, dst_pos + 8);\

LOAD32 (a3, b3, dst_pos + 12);\

\

__m128i c0, c1, c2, c3, e0, e1, e2, e3;\

LOAD32 (c0, e0, dst_pos + 16);\

LOAD32 (c1, e1, dst_pos + 20);\

LOAD32 (c2, e2, dst_pos + 24);\

LOAD32 (c3, e3, dst_pos + 28);\

\

__m256i w0 = _256i_combine_lo_hi (a0, c0);\

__m256i w1 = _256i_combine_lo_hi (a1, c1);\

__m256i w2 = _256i_combine_lo_hi (a2, c2);\

__m256i w3 = _256i_combine_lo_hi (a3, c3);\

__m256i w4 = _256i_combine_lo_hi (b0, e0);\

__m256i w5 = _256i_combine_lo_hi (b1, e1);\

__m256i w6 = _256i_combine_lo_hi (b2, e2);\

__m256i w7 = _256i_combine_lo_hi (b3, e3);\

\

transpose_avx_4x4_dwords (w0, w1, w2, w3);\

_256i_store (&d0 [dst_pos], w0);\

_256i_store (&d1 [dst_pos], w1);\

_256i_store (&d2 [dst_pos], w2);\

_256i_store (&d3 [dst_pos], w3);\

\

transpose_avx_4x4_dwords (w4, w5, w6, w7);\

_256i_store (&d4 [dst_pos], w4);\

_256i_store (&d5 [dst_pos], w5);\

_256i_store (&d6 [dst_pos], w6);\

_256i_store (&d7 [dst_pos], w7);\

} while (0)

MOVE256 (0);

MOVE256 (32);

#undef LOAD32

#undef MOVE256

}

}

};And this is the result:

24Read8_Write32_AVX_Unroll: 109

This is the absolute winner indeed. The performance is really impressive. It is six times faster than what we started with. The achieved de-multiplexing speed is 18.8 Gbytes/sec, or 73,400 times faster than the transmission speed of the E1 stream. We write 7.22 bytes every CPU cycle.

In case someone is interested in the assembly listing for this code, it can be found in the repository. A little bit of register spill is visible there, so it is possible that performance can still be improved slightly.

What is the speed limit?

It is interesting to compare the achieved speed with the theoretical speed limit. In our case this limit is the

speed of direct data copy, without transposition. It is also interesting

what the overhead of the measurement framework is – sometimes testing code can be slower than the code being tested.

Let’s write a Null version, which does nothing, and a Copy version, which copies the data straight to the destination:

class Null: public Demux

{

public:

void demux (const byte * src, size_t src_length, byte ** dst) const

{

assert (src_length == NUM_TIMESLOTS * DST_SIZE);

}

};

class Copy: public Demux

{

public:

void demux (const byte * src, size_t src_length, byte ** dst) const

{

assert (src_length == NUM_TIMESLOTS * DST_SIZE);

for (size_t dst_num = 0; dst_num < NUM_TIMESLOTS; dst_num ++) {

memcpy (dst[dst_num], src + dst_num * DST_SIZE, DST_SIZE);

}

}

};In case memcpy happens to be slow, let’s make an AVX-optimised copy routine as well:

class Copy_AVX: public Demux

{

public:

void demux (const byte * src, size_t src_length, byte ** dst) const

{

assert (src_length == NUM_TIMESLOTS * DST_SIZE);

assert (DST_SIZE % 32 == 0);

for (size_t dst_num = 0; dst_num < NUM_TIMESLOTS; dst_num ++) {

byte * d = dst [dst_num];

for (size_t dst_pos = 0; dst_pos < DST_SIZE; dst_pos += 32) {

_256i_store (d + dst_pos,

_mm256_load_si256 ((__m256i const *) (src + dst_num * DST_SIZE + dst_pos)));

}

}

}

};(the entire code is here)

To run it, we’ll have to comment out the call to check() in measure() and align the source matrix by 32.

This is what we get:

4Null: 1

4Copy: 90

8Copy_AVX: 56

The impact of the management framework is negligible, and our code runs with almost identical speed as memcpy-based

copy and with half the speed of the well-optimised memory copy. We’ve got very close to the theoretical limit of

possible performance.

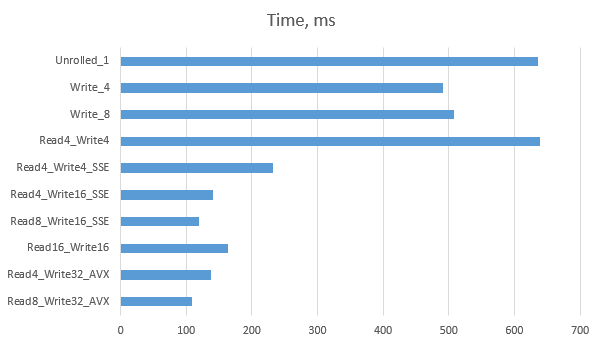

Results summary

Here are all the results we’ve got in C, in a table:

| Version | Time |

|---|---|

| Reference | 1367 |

| Src_First_1 | 987 |

| Src_First_2 | 986 |

| Src_First_3 | 1359 |

| Dst_First_1 | 991 |

| Dst_First_1a | 763 |

| Dst_First_2 | 766 |

| Dst_First_3 | 982 |

| Dst_First_3a | 652 |

| Unrolled_1 | 636 |

| Unrolled_1_2 | 632 |

| Unrolled_1_4 | 636 |

| Unrolled_1_8 | 635 |

| Unrolled_1_16 | 635 |

| Write_4 | 491 |

| Write_8 | 508 |

| Read4_Write4 | 638 |

| Read4_Write4_SSE | 232 |

| Read4_Write16_SSE | 141 |

| Read8_Write16_SSE | 120 |

| Read16_Write16_SSE | 163 |

| Read4_Write32_AVX | 138 |

| Read8_Write32_AVX | 109 |

And here is the graph with today’s results:

Conclusions

-

Java is fast but C++ is faster. Well, sometimes.

-

Our current speed is 6 times higher than the fastest version in C until now, and 26 times faster than where we started in Java

-

This improvement was achieved at a cost of portability

-

The SSE and AVX are indeed powerful tools to make programs faster; the fastest execution achieved without SSE was 494 ms.

-

The AVX as a rule is faster than the SSE, but it isn’t twice as fast (as one might hope) – we managed to achieve 120 ms using SSE and 109 ms using AVX

-

On an AVX machine it makes sense to compile SSE code with AVX instruction set enabled; it improves performance;

-

The ultra-fast programs with SSE/AVX look slightly less readable; they are more prone to errors and impose additional alignment requirements on the data. One must really think twice if making the program run four times faster is worth it.

Coming soon

Until now our programs ran in the artificial environment where all the data was in L1 cache. When the data doesn’t fit in cache, some of our optimisations may not work; some may even harm the performance. I’m going to measure performance on bigger volumes of data and check what can be done.