I once had to calculate a sum of a vector of integers.

This sounds unusual. Who ever wants to do this in real life? Normally, we only see code like this as primary school assignments or compiler benchmarks. However, this time it happened in real life.

Well, the actual task was to verify the IP header checksum, which is a ones’ complement sum of two-byte words. Simply speaking, it means adding together all the words and all the carry bits produced in the process. This procedure has several nice features:

-

it can be done very efficiently using the

ADCprocessor instruction (unfortunately, this feature is not accessible from C) -

it can be done on any size words (you can add eight-byte values if you wish, as long as you reduce the result to two bytes and add all the overflow bits together)

-

it is insensitive to the endianness of the processor (very surprising, but true).

There was one important requirement: the input data was not aligned (the IP frames as received by hardware or read from a file).

I didn’t have to bother about portability, as the only platform the code had to run was Intel x64 (Linux and GCC 4.8.3). Intel has no restrictions on the alignment of integer operands (an unaligned access used to be slow, but isn’t anymore), and, since the endianness was not important, the little-endian case was also all right. So I quickly wrote:

_Bool check_ip_header_sum (const char * p, size_t size)

{

const uint32_t * q = (const uint32_t *) p;

uint64_t sum = 0;

sum += q[0];

sum += q[1];

sum += q[2];

sum += q[3];

sum += q[4];

for (size_t i = 5; i < size / 4; i++) {

sum += q[i];

}

do {

sum = (sum & 0xFFFF) + (sum >> 16);

} while (sum & ~0xFFFFL);

return sum == 0xFFFF;

}The source code and assembly output can be found in the repository.

The most common size of an IP header is 20 bytes (5 double words, which I’ll call simply words) – that’s why the code looks like this. In addition, the size can never be less than that – this is checked before calling this function. Since IP header can never be longer than 15 words, the number of loop iterations is between 0 and 10.

This indeed isn’t portable – accessing arbitrary memory using pointers to 32-bit values is known to fail on some processors, such as most, if not all, RISC ones. However, as I said before, I never expected this to be an issue on x86.

And, of course (otherwise there wouldn’t have been a story to tell), the reality proved me wrong, as this code crashed with a SIGSEGV.

A simplification

The crash only happened when the loop was actually executed, which means that the headers were longer than 20 bytes. In real life this might be very rare case, but I was lucky

as my test data contained such headers. Let’s simplify our code to only contain this loop. We’ll write it in plain C and split it in two files

to avoid inlining. Here is sum.c:

#include <stdlib.h>

#include <stdint.h>

uint64_t sum (const uint32_t * p, size_t nwords)

{

uint64_t res = 0;

size_t i;

for (i = 0; i < nwords; i++) res += p [i];

return res;

}and here is main.c:

#include <stdint.h>

#include <stdio.h>

extern uint64_t sum (const uint32_t * p, size_t nwords);

char x [100];

int main (void)

{

size_t i;

for (i = 0; i < sizeof (x); i++) x [i] = (char) i;

for (i = 0; i < 16; i++) {

printf ("Trying %d sum\n", (int) i);

printf ("Done: %d\n", (int) sum ((const uint32_t*) (x + i), 16));

}

return 0;

}This code SIGSEGV’s inside sum when i equals 1.

The investigation

The code of the sum function is surprisingly long, so I’ll only show the main loop:

.L13:

movdqa (%r8), %xmm2

addq $1, %rdx

addq $16, %r8

cmpq %rdx, %r9

pmovzxdq %xmm2, %xmm1

psrldq $8, %xmm2

paddq %xmm0, %xmm1

pmovzxdq %xmm2, %xmm0

paddq %xmm1, %xmm0

ja .L13The compiler was clever. Too clever, if you ask me. It used SSE (it was allowed to do so, because I used it elsewhere and had -msse4.2 in my command line).

This code reads four values at a time (movdqa), then converts them to 64-bit format in two registers (two pmovzxdq instructions and a psrldq) and adds

to the current sum (%xmm0). After the loop it adds the accumulated values together.

This looks like a valid optimisation for the case when the word count is big, which is not our case. The compiler has no way to establish the typical number of loop iterations, that’s why it optimises for the highest benefits, correctly concluding that when the word count is small, so is the loss from the excessive optimisation. We’ll test later if there is such a loss and how big it is.

What can possibly crash in this code? We quickly establish that it is that movdqa instruction. Just like most of SSE instructions that access memory,

it requires 16-byte alignment of the source argument address. But we can’t expect such alignment from the uint32_t pointer, so how could this instruction be used at all?

The compiler actually takes care of the alignment. Before running the loop, it calculates how many words must be processed before the loop starts:

testq %rsi, %rsi ; %rsi is n

je .L14

movq %rdi, %rax ; %rdi is p

movq %rsi, %rdx

andl $15, %eax

shrq $2, %rax

negq %rax

andl $3, %eaxOr, in more conventional notation,

if (nwords == 0) return 0;

unsigned start_nwords = (- (((unsigned)p & 0x0F) >> 2)) & 3;This produces 0 if p ends with 0, 1, 2, or 3 in hex, 3 if it ends with 4 to 7, 2 for 8 to B and 1 for C to F.

After these first words have been processed, we can run the loop (provided that the number of remaining words is at least 4, and taking care of the leftovers).

In short, this code aligns the pointer to 16, but only provided that it is already aligned by 4.

Suddenly, our x86 behaves just like RISC: it crashes when a pointer to uint32_t is not aligned by 4.

Simple fixes do not work

No simple manipulation with this function resolves the problem. We can, for instance, declare the p parameter as char* as a naïve attempt

to “explain to the compiler the arbitrary nature of the pointer”:

uint64_t sum0 (const char * p, size_t nwords)

{

const uint32_t * q = (const uint32_t *) p;

uint64_t res = 0;

size_t i;

for (i = 0; i < nwords; i++) res += q [i];

return res;

}Or, we can replace indexing with the pointer arithmetic:

uint64_t sum01 (const uint32_t * p, size_t n)

{

uint64_t res = 0;

size_t i;

for (i = 0; i < n; i++) res += *p++;

return res;

}or do both:

uint64_t sum02 (const char * p, size_t n)

{

uint64_t res = 0;

size_t i;

for (i = 0; i < n; i++, p += sizeof (uint32_t))

res += *(const uint32_t *) p;

return res;

}Neither of these modifications help. The compiler is clever enough to get rid of all the syntax sugar and reduce the code to basics. All these versions crash with SIGSEGV.

What the standard says

This seems like a rather nasty trick of the compiler. The transformation it performed on the program contradicts to the usual expectations of a programmer who is used to x86. Is the compiler actually allowed to do this? To answer this, we’ll have to look at the standard.

I’m not going to dive deep into various standards of C and C++. Let’s look at one of them, that of C99, or, more specifically, at the latest publicly available version of the C99 standard (2007).

It introduces the concept of alignment:

3.2

alignment

requirement that objects of a particular type be located on storage boundaries with addresses that are particular multiples of a byte address

This concept is used when defining pointer conversion:

6.3.2.3

A pointer to an object or incomplete type may be converted to a pointer to a different object or incomplete type. If the resulting pointer is not correctly aligned for the pointed-to type, the behavior is undefined. Otherwise, when converted back again, the result shall compare equal to the original pointer. When a pointer to an object is converted to a pointer to a character type, the result points to the lowest addressed byte of the object. Successive increments of the result, up to the size of the object, yield pointers to the remaining bytes of the object.

And also when talking about pointer dereferencing:

6.5.3.2 Address and indirection operators

If an invalid value has been assigned to the pointer, the behavior of the unary * operator is undefined.87)87) Among the invalid values for dereferencing a pointer by the unary * operator are a null pointer, an address inappropriately aligned for the type of object pointed to, and the address of an object after the end of its lifetime.

If I understand these clauses correctly, converting pointers in general (except for converting anything to char *) is a dangerous business.

The program is allowed to crash right there, during conversion. Alternatively, conversion may succeed, but produce invalid value that causes crash

(or rubbish as a result) during dereferencing. In our case, either may happen if the alignment requirement for uint32_t enforced by this compiler is different

from one (the alignment for the char*). Since the most natural alignment for uint32_t is 4, the compiler was completely correct.

The sum0 version, although it does not resolve the problem, is still better than the original sum: the latter required the pointer to be of the uint32_t* type already,

which required a pointer conversion in the calling code. This conversion may crash immediately, or produce an invalid pointer value. Let’s move the responsibility to deal

with the alignment to the sum function, and, therefore, replace sum with sum0.

These standard clauses explain why our attempts to fix the problem by playing with the types of pointers and the way they are calculated fail. No matter what we do to the

pointer, eventually it is converted to uint32_t*, which immediately signals to the compiler that the pointer is four-aligned.

There are only two solutions that work.

Disabling the SSE

The first isn’t really a solution – rather, a workaround. On x86 the alignment problems only happen when using SSE, so let’s disable it.

We can do it for the entire file where sum is declared, or, if this isn’t practical, only for that function:

__attribute__ ((target("no-sse")))

uint64_t sum1 (const char * p, size_t nwords)

{

const uint32_t * q = (const uint32_t *) p;

uint64_t res = 0;

size_t i;

for (i = 0; i < nwords; i++) res += q [i];

return res;

}This code is even less portable than the original one, since it uses a GCC-specific and Intel-specific attribute. This can be rectified by appropriate conditional compiling:

#if defined (__GNUC__) && (defined (__x86_64__) || defined (__i386__))

__attribute__ ((target ("no-sse")))

#endifHowever, this isn’t really of much help, since all it does is make the program compile on other compilers and other architectures, but not necessarily work there. It may still crash if the target processor is RISC, or if the compiler uses some other syntax to disable SSE.

Even if we keep within the limits of GCC and Intel, who can promise that another architecture, not called SSE, won’t be introduced ten years from now? After all, my original code could have been written 20 years ago when there was no SSE around (the first MMX is 1997).

Still, this program produces very nice code:

sum0:

testq %rsi, %rsi

je .L34

leaq (%rdi,%rsi,4), %rcx

xorl %eax, %eax

.L33:

movl (%rdi), %edx

addq $4, %rdi

addq %rdx, %rax

cmpq %rcx, %rdi

jne .L33

ret

.L34:

xorl %eax, %eax

retThis is exactly the code I had in mind when writing the function. I expect this code to run faster than the SSE-based one for small vector sizes, which is our case with IP. We’ll perform measurements later.

Using the memcpy

Another approach is to use memcpy. This function can copy the bytes representing a number into a variable of the corresponding type, no matter what the alignment is.

And it does this in fully standard-compliant way. This may seem inefficient, and 20 years ago it really was. These days, however, it doesn’t have to be

implemented as a procedure call at all; the compiler can treat it as an intrinsic, and replace with a memory-to-register load. The GCC definitely does.

It compiles the following code

uint64_t sum2 (const char * p, size_t nwords)

{

uint64_t res = 0;

size_t i;

uint32_t temp;

for (i = 0; i < nwords; i++) {

memcpy (&temp, p + i * sizeof (uint32_t), sizeof (temp));

res += temp;

}

return res;

}into the code similar to the original SSE one, except it uses movdqu instead of movdqa. This instruction allows misaligned data;

its performance varies. On some processors it is much slower than movdqa even when the data is actually aligned. On others it runs at virtually the same speed.

Another difference in the generated code is that it doesn’t even try to align the pointer. It uses movdqu on the original pointer even if it could align it and then use movdqa.

This means that this code, being more universal, may end up slower than original code on some inputs.

This solution is completely portable, for it can be used everywhere, even on RISC architectures.

Combined solution

The first solution seems to be faster on our data (although we haven’t measured it yet), while the second one is more portable. We can combine the two:

#if defined (__GNUC__) && (defined (__x86_64__) || defined (__i386__))

__attribute__ ((target ("no-sse")))

#endif

uint64_t sum3 (const char * p, size_t nwords)

{

uint64_t res = 0;

size_t i;

uint32_t temp;

for (i = 0; i < nwords; i++) {

memcpy (&temp, p + i * sizeof (uint32_t), sizeof (temp));

res += temp;

}

return res;

}This code will be compiled into a nice non-SSE loop on GCC/Intel, but will still produce a working (and fairly good) code on other architectures. This is the version I’m going to use in my project.

The code it produces for x86 is identical to that of sum1.

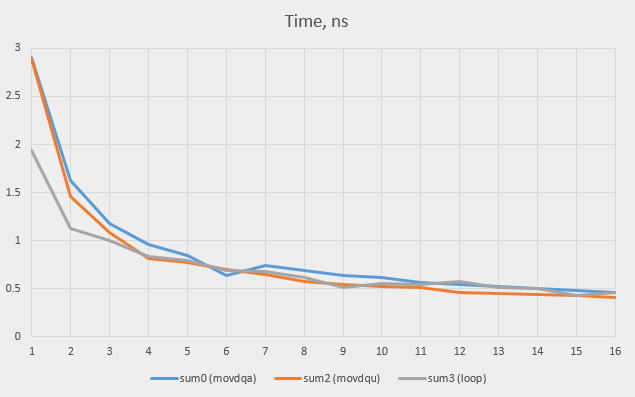

Measuring speed

We’ve seen that the compiler had full right to generate the code with movdqa. Was it also a good decision from performance point of view? Let’s measure the speed of all

our solutions. First, we’ll do it on fully aligned data (the pointer is aligned by 16). The figures are in nanoseconds per word added.

| Size, words | sum0 (movdqa) | sum1 (loop) | sum2 (movdqu) | sum3 (loop, memcpy) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2.91 | 1.95 | 2.90 | 1.94 |

| 5 | 0.84 | 0.79 | 0.77 | 0.79 |

| 16 | 0.46 | 0.45 | 0.41 | 0.46 |

| 1024 | 0.24 | 0.46 | 0.26 | 0.48 |

| 65536 | 0.24 | 0.45 | 0.24 | 0.45 |

This table confirms that on the very small word count (1) the ordinary loops run faster than the SSE-based versions, although the difference isn’t really very big (1 ns per word, and there is only one word).

The SSE wins on big word counts (1024 and more), and here the overall benefit may be big.

The speeds are almost equal, with a small advantage of SSE (movdqu) on medium-sized inputs (such as 16).

Let’s run the test for all the values between 1 and 16 and check where the break-even point is. The sum1 (non-SSE loop) and sum3 versions show very similar times

(which is to be expected since the code is identical; the time differences demonstrate the measurement accuracy of about 0.02 ns). That’s why we’ll only include

the final version (sum3):

We see that the simple loops win over SSE versions up to the word count of 3, after which the SSE versions start to take over (the movdqu version, as a rule,

being faster than the original movdqa).

I think that, without any additional information, a compiler is right in assuming that an arbitrary loop will execute more than three times, so its decision to use

SSE was completely correct. But why didn’t it go straight for movdqu option? Is there any reason to do movdqa at all?

We’ve seen that when the data is aligned, movdqu version runs at the same speed as movdqa on big word counts, and runs faster on small ones. The latter can be explained

by fewer instructions that precede the loop (no need to test alignment). What happens if we run the test on misaligned data? Here are the times for some options:

| Size, words | Offset 0 | Offset 1 | Offset 4 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| movdqa | movdqu | loop | movdqu | loop | movdqa | movdqu | loop | |

| 1 | 2.91 | 2.90 | 1.94 | 2.93 | 1.94 | 2.90 | 2.90 | 1.94 |

| 5 | 0.84 | 0.77 | 0.79 | 0.77 | 0.79 | 0.84 | 0.79 | 0.78 |

| 16 | 0.46 | 0.41 | 0.46 | 0.42 | 0.46 | 0.52 | 0.40 | 0.46 |

| 1024 | 0.24 | 0.26 | 0.48 | 0.26 | 0.51 | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0.47 |

| 65536 | 0.24 | 0.24 | 0.45 | 0.25 | 0.50 | 0.24 | 0.24 | 0.46 |

As we see, alignment introduces only slight variations in the times, except for one: movdqa version becomes a bit slower (0.52 ns instead of 0.46) at offset 4, size 16.

The direct loop is still the best solution on small word counts; movdqu is the best on big ones. The compiler wasn’t right using movdqa. A possible explanation

is that it is optimising for an older model of the Intel processor. The movdqu instruction used to work quite a bit slower than movdqa on Xeon processors,

even on fully aligned data. It looks like this isn’t the case anymore, so the compiler can be simplified (and the alignment requirements relaxed).

The original function

The original function that checks IP headers must now be re-written like this:

#if defined (__GNUC__) && (defined (__x86_64__) || defined (__i386__))

__attribute__ ((target ("no-sse")))

#endif

_Bool check_ip_header_sum (const char * p, size_t size)

{

const uint32_t * q = (const uint32_t *) p;

uint32_t temp;

uint64_t sum = 0;

memcpy (&temp, &q [0], 4); sum += temp;

memcpy (&temp, &q [1], 4); sum += temp;

memcpy (&temp, &q [2], 4); sum += temp;

memcpy (&temp, &q [3], 4); sum += temp;

memcpy (&temp, &q [4], 4); sum += temp;

for (size_t i = 5; i < size / 4; i++) {

memcpy (&temp, &q [i], 4);

sum += temp;

}

do {

sum = (sum & 0xFFFF) + (sum >> 16);

} while (sum & ~0xFFFFL);

return sum == 0xFFFF;

}If we’re scared of converting an unaligned pointer to uint32_t* (the standard talks about an undefined behaviour), it must look like this:

#if defined (__GNUC__) && (defined (__x86_64__) || defined (__i386__))

__attribute__ ((target ("no-sse")))

#endif

_Bool check_ip_header_sum (const char * p, size_t size)

{

uint32_t temp;

uint64_t sum = 0;

memcpy (&temp, p, 4); sum += temp;

memcpy (&temp, p + 4, 4); sum += temp;

memcpy (&temp, p + 8, 4); sum += temp;

memcpy (&temp, p + 12, 4); sum += temp;

memcpy (&temp, p + 16, 4); sum += temp;

for (size_t i = 20; i < size; i+= 4) {

memcpy (&temp, p + i, 4);

sum += temp;

}

do {

sum = (sum & 0xFFFF) + (sum >> 16);

} while (sum & ~0xFFFFL);

return sum == 0xFFFF;

}Both versions look very ugly, especially the second one. Both remind me of writing in pure assembly. However, this is the correct way of writing portable C.

Interestingly, even though we’ve established that the loop runs at the same speed as movdqu on the word count of 5, re-writing the function as one loop from 0 to size

makes it slower (typical times are 0.48 ns and 0.83 ns per word).

The C++ version

C++ allows us to write the same function in much more readable way by employing some template programming. We’ll introduce a generic type called const_unaligned_pointer:

template<typename T> class const_unaligned_pointer

{

const char * p;

public:

const_unaligned_pointer () : p (0) {}

const_unaligned_pointer (const void * p) : p ((const char*)p) {}

T operator* () const

{

T tmp;

memcpy (&tmp, p, sizeof (T));

return tmp;

}

const_unaligned_pointer operator+ (ptrdiff_t d) const

{

return const_unaligned_pointer (p + d * sizeof (T));

}

T operator[] (ptrdiff_t d) const { return * (*this + d); }

};This is just a skeleton. The real definition must include equality test, a “minus” operator for two pointers, a “plus” operator in other direction, some conversions and, probably, other stuff.

This type allows our function to look very close to the version we started with:

bool check_ip_header_sum (const char * p, size_t size)

{

const_unaligned_pointer<uint32_t> q (p);

uint64_t sum = 0;

sum += q[0];

sum += q[1];

sum += q[2];

sum += q[3];

sum += q[4];

for (size_t i = 5; i < size / 4; i++) {

sum += q[i];

}

do {

sum = (sum & 0xFFFF) + (sum >> 16);

} while (sum & ~0xFFFFL);

return sum == 0xFFFF;

}This code produces exactly the same assembly as the code with memcpy and, obviously, runs at the same speed.

Some more templates

Our code only reads unaligned data, so the const_unaligned_pointer class is sufficient. What if we wanted to write it as well? We can make a class for that too, but

in this case we need two classes: one for a pointer and one for the l-value produced while dereferencing this pointer:

template<typename T> class unaligned_ref

{

void * p;

public:

unaligned_ref (void * p) : p (p) {}

T operator= (const T& rvalue)

{

memcpy (p, &rvalue, sizeof (T));

return rvalue;

}

operator T() const

{

T tmp;

memcpy (&tmp, p, sizeof (T));

return tmp;

}

};

template<typename T> class unaligned_pointer

{

char * p;

public:

unaligned_pointer () : p (0) {}

unaligned_pointer (void * p) : p ((char*)p) {}

unaligned_ref<T> operator* () const { return unaligned_ref<T> (p); }

unaligned_pointer operator+ (ptrdiff_t d) const

{

return unaligned_pointer (p + d * sizeof (T));

}

unaligned_ref<T> operator[] (ptrdiff_t d) const { return *(*this + d); }

};Again, this code just demonstrates the idea; much more is needed to make it suitable for production use. Let’s try a simple test:

char mem [5];

void dump ()

{

std::cout << (int) mem [0] << " " << (int) mem [1] << " "

<< (int) mem [2] << " " << (int) mem [3] << " "

<< (int) mem [4] << "\n";

}

int main (void)

{

dump ();

unaligned_pointer<int> p (mem + 1);

int r = *p;

r++;

*p = r;

dump ();

return 0;

}Here is the output:

0 0 0 0 0

0 1 0 0 0

We could have written

++ *p;but this requires defining operator++ in unaligned_ref.

The generated code looks very good:

call _Z4dumpv

addl $1, mem+1(%rip)

call _Z4dumpvConclusions

-

Alignment issues are not only relevant for RISC processors. SSE makes them valid for x86, too (in both 32 and 64-bit mode).

-

In our case the compiler was correct in using SSE in the generated code. However, it could have used an unaligned access – not only would it be more robust, it also would be faster (and would mask the problem, so that the program would crash some other time).

-

There is a benefit in writing the code as portable as is practically possible: your own processor may suddenly start behaving like a totally different one.

-

There is a lot of code lying around, which was written twenty years ago and only ever ran on Intel. This code may suddenly crash in a similar fashion. One practical advice is to disable all possible instruction set extensions while compiling such code – however, even that may turn out insufficient.

-

This story demonstrates that there is something useful in code coverage tools. Here I was lucky that the input data caused all the code to execute. It might be different some other time.

Update

On /r/cpp on reddit, OldWolf2 pointed out that the checksum code contained a bug, in the last line:

} while (sum & ~0xFFFFL);He is correct: 0xFFFFL has type unsigned long, which is not necessarily the same as uint64_t. A long might be 32 bits, in which case the bit inversion would happen

before expansion to 64 bits, and the actual constant used in the test would be 0x00000000FFFF0000. It is easy to construct an input where such test would fail – for instance,

for the array of two words: 0xFFFFFFFF and 0x00000001.

We can either perform bit inversion after cast:

} while (sum & ~(uint64_t) 0xFFFF);or use comparison instead:

} while (sum > 0xFFFF);Interestingly, GCC produces shorter code in the second case. Here is the version with the bit test:

.L15:

movzwl %ax, %edx

shrq $16, %rax

addq %rdx, %rax

movq %rax, %rdx

xorw %dx, %dx

testq %rdx, %rdx

jne .L15And this is with comparison:

.L44:

movzwl %ax, %edx

shrq $16, %rax

addq %rdx, %rax

cmpq $65535, %rax

ja .L44Comments are welcome below or on reddit.